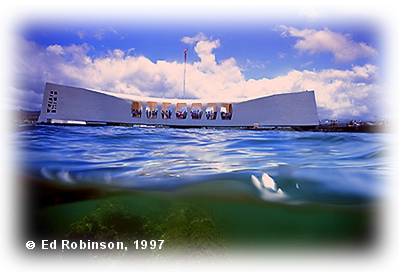

USS Arizona Memorial

by Ed Robinson

Once in a while the adage "being in the right place at the right time" will manifest in my life. One such instance was back in 1991 when someone recommended my name to the editors of Natural History magazine while they were in the planning stage of an article on the USS Arizona, in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

I was contacted, and subsequently hired to photograph one of the most famous, and certainly the most widely visited ship wreck in the world. The real uniqueness of this assignment is that I would be allowed to spend two days divining and photographing a wreck that is simply not available to myself, or any other diver that is not on official business. In fact, security is so strict on the wreck that my dives were constantly being monitored by several park divers who's job was to make sure I did not enter or disturb any part of this National Memorial. And I understand why, since there are over a thousand sailors still entombed within the ship.

But this article is not about the story of the sinking of the USS Arizona. National History magazine has hired me to photograph the ship and marine life on it, to accompany a story about the wreck itself. My biggest concern in photographing the Arizona is the water visibility. I don't know how good or bad it can be, but for my two days of diving the visibility ranged from about ten feet in open areas to two or three feet as I dropped into deeper water. To be honest, I was disoriented and often lost most of the time I was underwater. On the plus side, the water was very still so I didn't have current or surge to contend with.

My mood during the dives was always somber as I could not remove from my mind the horrific events that bent the metal I was seeing and ended the lives of the men that were located beneath the deck I was swimming over.

As wrecks go, the Arizona was not very attractive. Since most of the super structure and gun turrets were stripped for parts, much of the deck appears flat with low protrusions scattered along it. The only real sign that she was once a war ship is the stern turret with three large guns, hidden in the murk of two foot visibility.

The real story, for my dives, is the profusion of marine life the covers the ship. Every where I turned I found feather worms, bright encrusting sponges, delicate sea anemones, and sea cucumbers that must have been six feet long. Fish life was also abundant, although the sound of my bubbles kept most of them outside my vision in the murky waters. A number of times a large school of surgeonfish would swarm in, and out, of my sight too quickly to even identify which fish I was seeing.

Sergeant Major damselfish (mamo) were one of the better represented fish species and I noticed an interesting difference in their behavior, when compared to their brothers on the open reef. During mating season the Sgt. Major damselfish will lay a carpet of eggs on a smooth surface. Then the male fish will continuously hover over the eggs and chase off any other species of fish that comes near. I observed a number of egg mats on the deck of the Arizona but the male protector fish was nowhere to be seen. My conclusion from this observation is that butterfly fish and wrasse fish that I normally see attacking the reef Sgt. Major eggs are not present on the Arizona.

I also enjoyed the wide variety of sessile marine life that I am not used to seeing, but which is probably common in all bay-like areas (in which I rarely dive.) Many areas were covered in mats of tiny, brightly colored sea anemones, intermixed in beds of red encrusting sponge. The wreck seemed mystical too, as I would catch distant movement from hundreds of feather worms quickly retracting from my presence.

As eerie and moody as the diving was for me, my time spent on the USS Arizona will always be among my favorite dives of all time. I was truly touched by my experience.

Photos & text © Ed Robinson